Trending:

Centenarian Krishen Khanna: A visual raconteur of ordinary lives

Khanna witnessed upheavals of history, was uprooted and yet carved a distinct new identity for himself.News Arena Network - Chandigarh - UPDATED: July 4, 2025, 06:32 PM - 2 min read

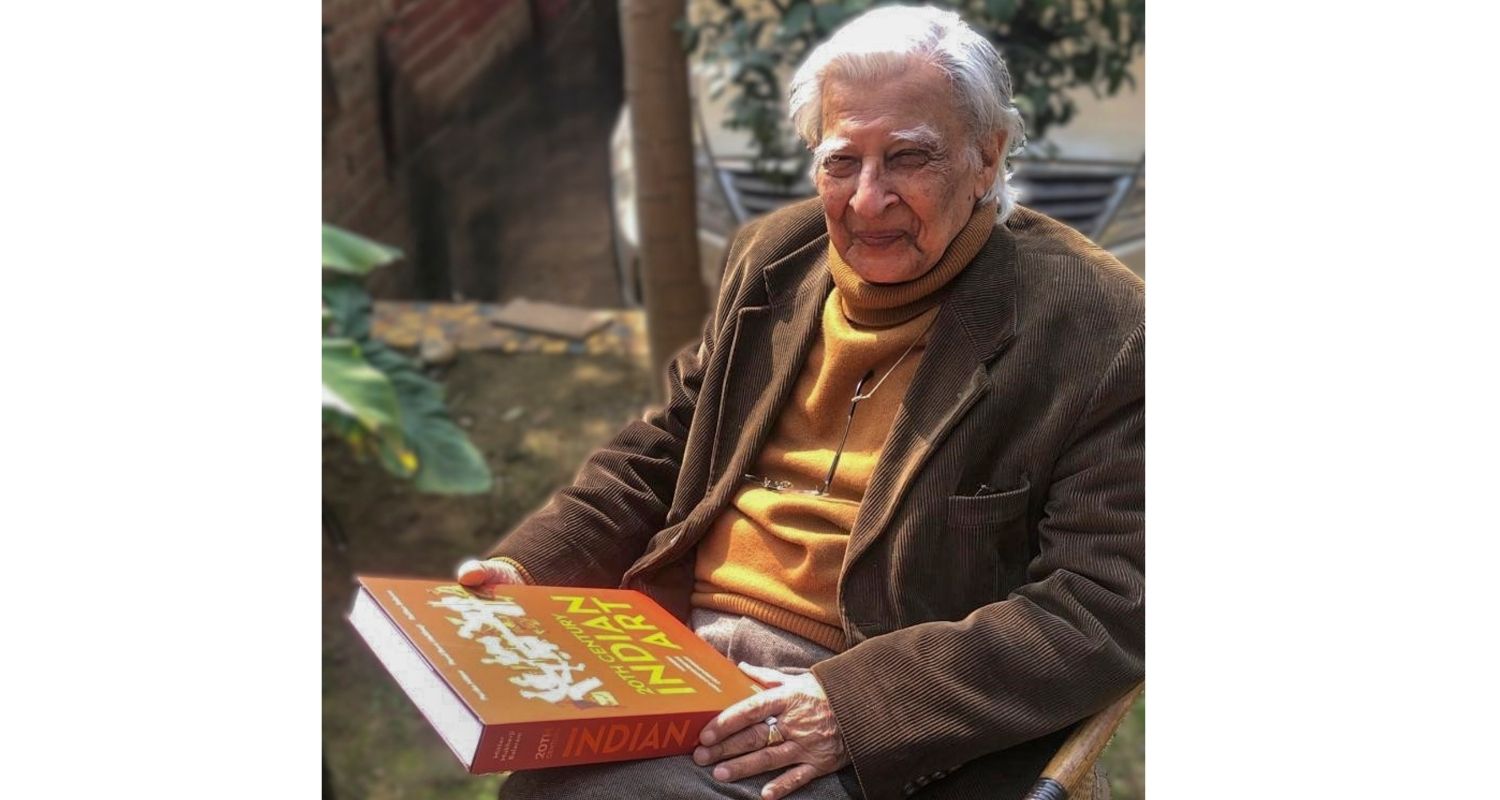

Krishen Khanna. File photo.

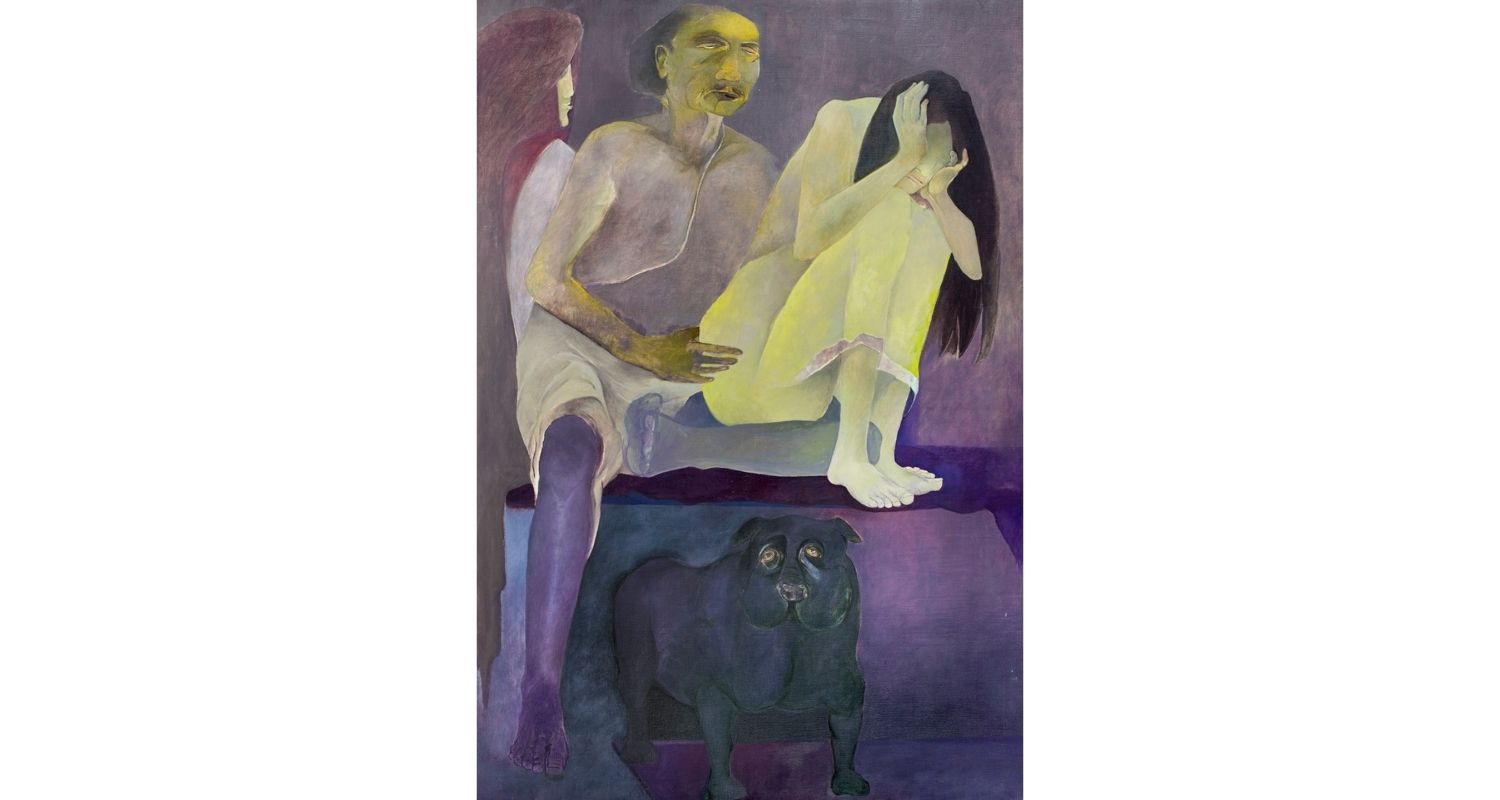

When the modernists were moving towards complete abstraction, Krishen Khanna stuck to his abstractive figurative artwork, depicting ordinary people’s lives. His celebrated works of the ordinary bandwallas, dhabewalas, truck drivers and street labourers became iconic. Khanna is among the very few artists who documented the agony of the partition of India on his canvas to immortalise common man’s suffering of forced uprooting. The self-taught artist’s hundredth birthday is celebrated by the artist fraternity and art lovers on July 5.

Khanna witnessed upheavals of history, was uprooted and yet carved a distinct new identity for himself—this makes his centenary special and unparallelled. Born on 5 July, 1925, he is the only surviving artist of the famous Progressive Artists Group that gave a distinct identity to Indian modern art. His contemporaries who greatly influenced Indian art; Souza, Hussain, Gaitonde, Raza and others have all passed away.

Khanna was born in Faisalabad (Lyallpur), now in Pakistan, in a well-to-do family.

The artist developed interest in drawing in his childhood. His family members used drawing as a leisure activity on Sundays. The emphasis was on practice, not on the quality produced. An ordinary object was taken as the subject of drawing.

Once his father brought home a copy of Da Vinci’s work, ‘The Last Supper’. Khanna was captivated by it. Gradually, the simple practice of drawing became an act of dedication for him. Making new discoveries and developing insights in the manner of looking at an object engaged him; not only in terms of geometrical considerations but in the colour matrix and the elusive co-ordination between the hand and the eye. He was fascinated by the immense potential of the point of a pencil in depicting varied shades of life. And the process of translation of what the eye could see by his hand. His effort was to master the fleeting moment of perfection in that coordination.

From Lyallpur his family moved to Lahore, where he joined a course in English Literature at the Government College, on his return from England, where he studied at the Imperial Service College and was a Rudyard Kipling scholar. His interest in drawing did not fade during his stint in England. In fact, his local guardian in England, a Christian family, gave him books of the Biblical myths; their visual interpretations that he encountered during this stay formed the foundation of his visual memory.

He was only 13 when he was sent to England. Back in Lahore, along with pursuing English Literature, he joined evening classes at the famous Mayo College to hone his skills in art. Very briefly he worked as a painter at Kapoor Art Press, Lahore.

The partition of 1947 displaced his family; they moved to Shimla. Khanna worked at the Grindlays Bank in Bombay where he befriended the Progressives and later at Madras from 1946-61, subsequently resigning from his job to devote himself to art.

Painter of the Partition

Khanna’s art bears imprints of the traumatic experience of the uprooting and the socio-political chaos of post-partition India. He was in his early 20s when he was uprooted from Lahore. It affected him deeply.

This experience influenced a large body of his work. His famous series on the bandwallahs, the truck drivers, and the disturbing visuals of people dislocated by the havoc caused by the Partition; carrying the void of up rootedness and unbearable grief, continue to haunt the viewer. The almost fading, distorted human figures are etched over dark backgrounds with their detached, hollow faces to make powerful visuals. They seem to be in a perpetual transit; floating in their up rootedness.

Khanna’s process of creation stems from the moments picked from memory and the observations transferred onto the canvas with spontaneity and exuberance, keeping the representational elements of his subject matter intact. The use of colour and his expressionist brushwork make the mundane rise to the challenge of the artistic.

“Letting the keen observations form into an image in your mind, that is how you tap visual language. It takes time,” says Khanna about his processes.

The displaced people were hundreds of truck drivers travelling in and out of Delhi, and the nameless, dressed- in- red uniforms bandwallahs, playing songs of rejoicing, forgetting their sad, deprived lives in that moment of sharing some stranger’s joys. The seemingly lost, forlorn figures of bandwallas in their bright, polished outfits affected Khanna for their unstated sadness. “They come from that part of Punjab I had known, they would rejoice for us. They had to hide their loss, their pain. How would they live (now)—nobody was paying them, living was more important, not playing music; they had to improvise, they came without anything, they had to look good, fighting their battles yet loving what they were doing. The whole family would come, even the old ones who would be asked to just strike the triangle once in a while. It’s fascinating to see how people who had nothing and yet loved what they were doing,” Khanna recounted in an interview.

These nuances about ordinary people’s lives that he internalised, lend his canvas the extra dimension. He was not illustrating or documenting their lives; his profound empathy made these frames immortal.

Also read: India’s Mohenjo-daro: The Harappan site of Dholavira

Most of the Sikhs who migrated from Pakistan became truck drivers— trucks became their new homes, like for the bandwallas others’ joys became their own. Khanna felt a deep sense of compassion for these lakhs of displaced people; they continued to people his creative space.

Bordering on the narrative, his works capture moments in history, like his famous painting Death of Gandhi does, much like photographs do, but his technique is not that of a photo-realist.

Noted artist late J. Swaminathan once observed, “What makes it art and lifts it out of the transient is the abiding elements of the tragic, sublime and the ridiculous, which are woven into it.”

A diverse journey

To limit his works to partition would be an injustice to the immense diversity of his works. Khanna has delved his hands in sculptures, graphics, studio photography and almost all creative mediums. His charcoal works are powerful statements of the times.

He first exhibited his works in 1949, when his first painting was bought by nuclear physicist Dr. Homi Bhabha. In 1955, Khanna held his first solo show at U.S.I.S., Madras and never looked back.

Khanna’s deep commitment to the pictorial space was not to be confined by the limits of the easel. He got an opportunity to break free of this confinement. In the early 80s, the chairman of ITC showed him the blank, dome-like space of about 4000 square feet on the ceiling of ITC Maurya, New Delhi. He asked, if he would like to paint the ceiling with murals?

To scale up the visualisation, from the size of an easel to 4000 square feet was unnerving even for an artist of Khanna’s calibre. After completion, the murals on the dome turned out to be a kaleidoscopic wonder. Called ‘The Great Procession’, the hand-painted labour of love offers hundreds of perspectives based on the five elements of life, encompassing all the nine rasas. A visual narrative is woven using Chinese traveller, Fa Hien, as a purveyor, who finds the footprints of time in the eternal march of Indian civilisation.

Actively creating shows till he turned 97, in different mediums Khanna has lost count of how many canvases he has painted; perhaps over four thousand. His works are sold globally and are displayed in all the major museums of the world. His artistic journey continues to create new milestones. He has lived a life of timelessness in time spanning to a century, following his passion. He wishes to die somewhere near his easel, with an unfinished painting.

Recognising his immense contribution to Indian art, the Government of India bestowed several honours upon him including the Lalit Kala Ratna from the President of India in 2004, the Padma Shri in 1990 and the Padma Bhushan in 2011.

By Vandana Shukla