Trending:

Memory and fiction—aching loss of Partition in literature

Most of the authors had fled their homeland—from what came to be known as Pakistan. After regaining some semblance of normalcy, they started to record the events in the form of novels and short stories.News Arena Network - Chandigarh - UPDATED: August 17, 2025, 02:13 PM - 2 min read

Partition continues to haunt—not just as a bloody chapter of our history but as a lived reality.

“That sense of belonging, which I had in India, I knew I couldn’t find anywhere else… I can never be a complete person now. I can’t ignore partition. It’s part of me. I feel rudderless. If there had been no Partition, I might have been a married man with all the paraphernalia… the creation and existence of Pakistan has damaged a part of my psyche. I simply cannot pretend it doesn’t exist. I cannot pretend that life goes on…”

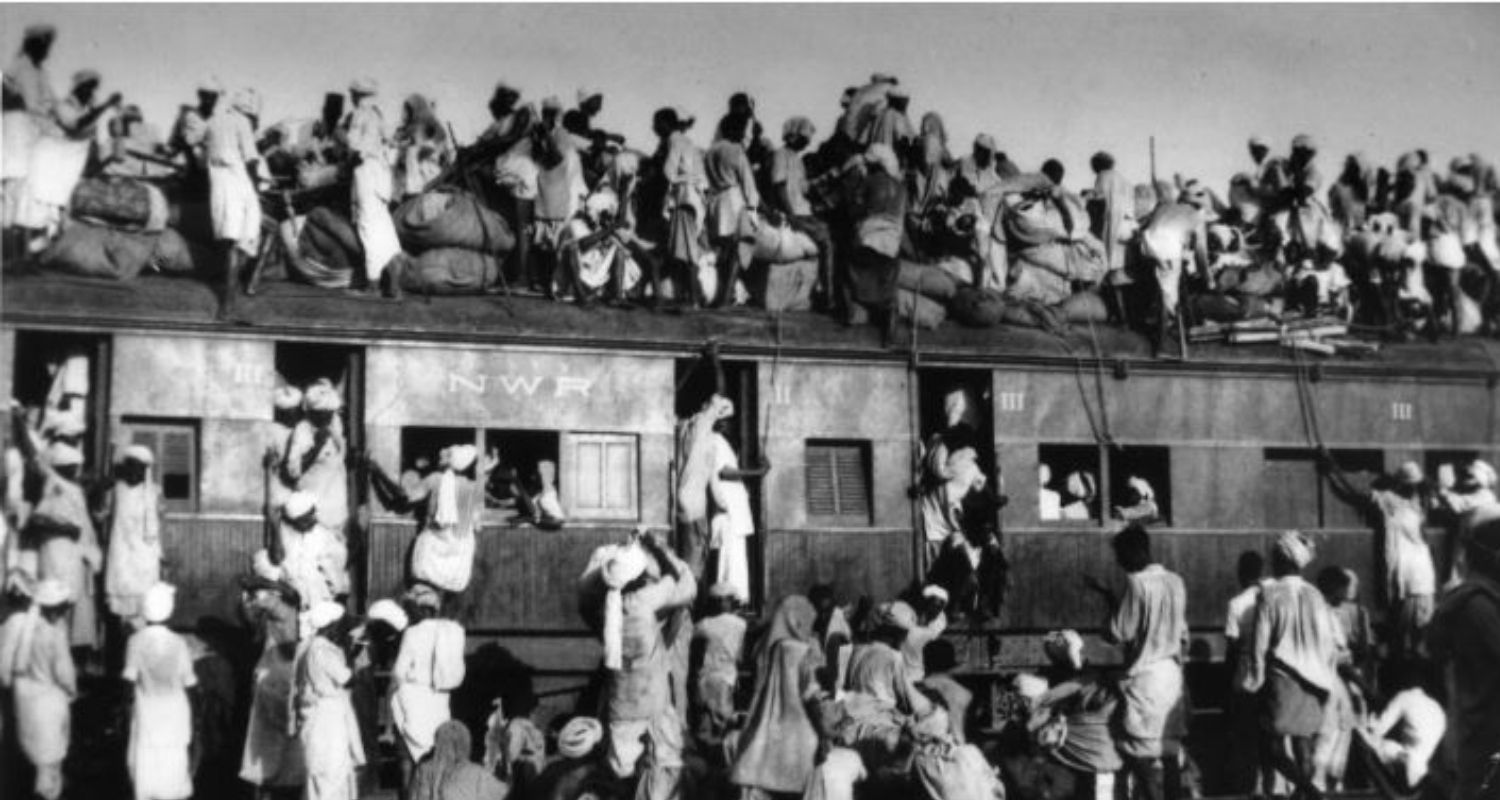

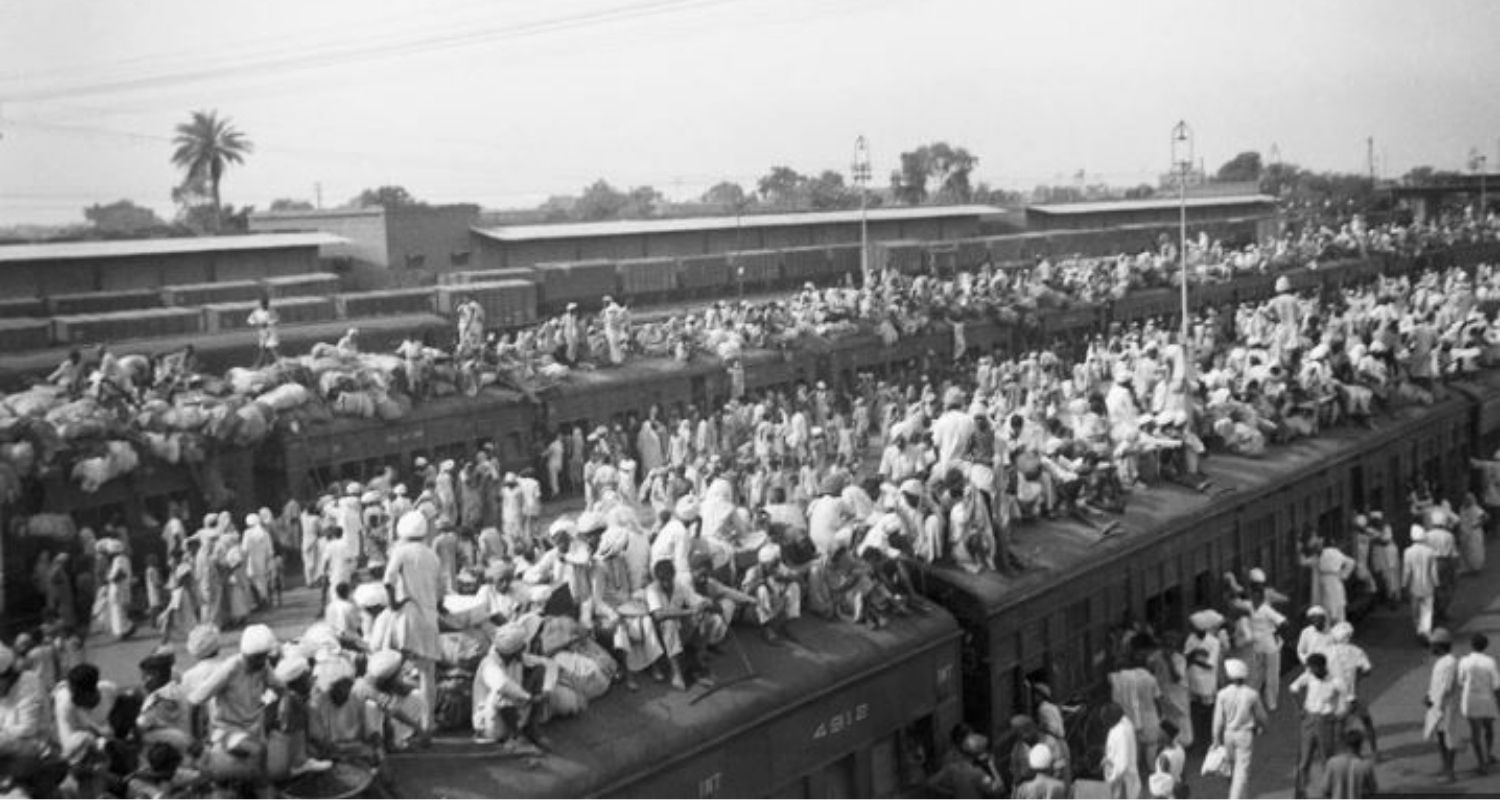

Unlike the honest admission by Rashid, in VS Naipaul’s ‘India A Million Mutinies Now’, the Partition of India in 1947 was reduced to a footnote in our history books. To pretend as though the communal violence that resulted in one of the greatest upheavals in recorded history of the sub-continent was of little significance. To make people believe that the Partition that triggered the largest forced migration of humanity on the globe—uprooting over 12 million people and killing approximately one million in the most brutal manner would not affect the future of the nation—was a fallacy.

The communal holocaust that preceded and followed the Partition remained deeply inscribed in the memories of the people. Families that directly suffered and those who witnessed the savagery—both failed to erase it from their psychological and emotional landscape. It created a spiral effect.

Writers, poets and artists kept these memories alive on both sides of the border. Baffled by the unprecedented barbarity and erosion of human values witnessed during July-September 1947, writers have since been trying to figure out the genesis of unprecedented cruelty of the neighbours, friends and acquaintances—people they trusted. In their attempt to bring the Partition back from the footnotes to the main discourse—at times, they revive the painful and unpleasant memories from a bloody chapter of our history.

Shock and gore

Most of these authors had fled their homeland—from what came to be known as Pakistan. After regaining some semblance of normalcy, they started to record the events in the form of novels and short stories. These novels and stories can be best described as a reaction to the disillusionment of the times. After the first shock was absorbed, it left them with a void. The country had realised its long-cherished dream of independence but the delicate threads of trust and confidence were snapped.

Alienation of the masses from the leaders - preoccupied with ‘nation building’ was another factor that accentuated this void. A deep quest pervaded these writings for the lost world. KA Abbas, Khushwant Singh, Bhisham Sahni and Manohar Malgonkar are among the first few writers who took up the theme of Partition in ‘Inquilab’, ‘A Train to Pakistan’, ‘We Have Arrived in Amritsar’ and ‘A Bend in the Ganges’, respectively.

These authors did not have the luxury of objectivity; their datelines were too close, resulting in a myopic vision of the violent history. These novels, including ‘The Dark Dancer’ by Balachandra Rajan, suffer from the hangover of the idealism of cultural synthesis—of the much-touted ‘Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb’, which was torn to pieces during the communal riots of the Partition. Only Malgonkar attempts to outgrow these shadows by questioning the utility and practicability of the theory of non-violence; suggesting that only by giving lip service to ideals, human nature is not changed.

‘Train To Pakistan’ can be credited for bringing the theme of Partition to the mainstream discourse. The novel that evokes the communal atmosphere of the times with powerful imagery in lyrical prose gained high popularity. Singh, being a successful journalist, managed to get the focus on the theme of communal violence.

Lack of nuances and Manto

Saadat Hasan Manto’s ‘Siyah Hashiye’, with its stark realism of journalistic kind of direct reporting of communal violence, became the most controversial book on the Partition. Manto became a cult writer with a huge following.

The phenomenon of Manto also ripped open many hypocrisies of the intelligentsia of the times who were professing the ideals of a secular India. Chinks appeared between their professed writings and their personal realities. It exposed a different picture of the stories that writers like Manto were writing.

Also read: Why journalists become best-selling authors

When Manto was charged of obscenity and a legal case was going on in the courts, none of his friends from the Progressive Writers’ Association stood for him; later he was expelled from PWA for his short stories Bu’, ‘Kali Salwar’ and ‘Khol Do’. The PWA had all the famous secular writers of the times, including Faiz. Secondly, post-Partition, Manto decided to migrate to Pakistan. It severed the already strained fragile fabric of trust—deepening the void of secular ideals. Manto stood against the tides of communal violence; his escape under the same forces disillusioned readers.

Charged with titillation and obscenity, Manto’s unprecedented success in underlining the communal issues of society—exposing its hidden shades–goes beyond doubt. His reportage-like technique was copied like the popular formula of a super hit film, though with little success. Manto focused on a slice of the communal events, showing the debased, predatory aspect of humanity, ignoring several other hues. It became a limiting factor for the Partition literature. It lacked nuances. Interest in Manto’s stories was revived several decades later by theatre and cinematic adaptations of his short stories.

The other voices—women, children, mental health

Urvashi Butalia’s ‘The Other Side of Silence’ archived the survivor’s tales, documenting the ground realities of displacement and the unaccounted loss of family for 75,000 women—many of whom abducted, raped and forcible married to their rapists and abductors. This book removed the blanket of silence from their suppressed voices. It recognised the ramifications of violence in women’s social and psychological realms. Another important novel, ‘Sunlight On A Broken Column’, written from the perspective of a 15-year-old Muslim orphan girl from an affluent Taluqdar family of Lucknow, by Attia Hosain, exposes the hypocrisies of the politically influential Taluqdars who were instrumental in dividing the country, and leaving behind millions of poor Muslims to face consequences—simmering with communal violence. It is one of the most honest accounts on what happened in the drawing rooms of the rich and powerful—exposing their hypocrisies in their personal realms while they advocated for two independent nations.

Seen from the eyes of a Parsi child of 10, the first-person account of communal violence of Lahore that preceded the Partition in ‘Cracking India’, originally published as ‘Ice Candy Man’, by Bapsi Sidhwa, is another important book.

Unlike Manto’s acidic satire ‘Toba Tek Singh’, Anirudh Kala in his sensitively written short story collection ‘The Unsafe Asylum’ explores the impact of the bureaucratic decision of exchange of mental health patients from the only mental health hospital of Lahore. Nuanced with deep insight and an interplay of memory, the stories highlight the profound impact Partition had on the mental health of ordinary people. While Punjab dominated narratives on the Partition literature, Amitav Ghosh’s brilliant novel ‘The Shadow Lines’ explores memory, history and the impact of Partition on the lives of a Bengali family who had to leave behind everything it owned in the divided East Pakistan, which later became Bangladesh.

From the other side of the border

Writers from Pakistan looked at the Partition with a different lens—tinge of guilt gives their writings a deeper tug at the heartstrings. These writings are free of the burden of hypocrisy of non-violence advocated by Indian leadership. Since the demand for a separate country based on religious identity had come from the All-India Muslim League and several violent attacks like the Direct Action Day of August 16, 1946, were planned and executed in Calcutta by the League, surpassing the savagery of the medieval Islamic invaders, it forced writers in the newly carved Pakistan to look within their quest for answers.

One of the most important novels in Urdu on the Partition, ‘Udas Naslein’ by Abdullah Hosain, covers a vast canvas—beginning from the WWI and culminating in the Partition; it is a poignant attempt at the quest for identity and the genesis of communal violence. The novel was later translated into English by Gillian Wright. ‘Basti’ by Intezar Husain is another important work on the theme, apart from many short stories he penned. Jamila Hashmi uses imagery from Hindu mythology to convey the loss of a syncretic culture in ‘Banishment’, a story of an abducted woman at the crossroads of memory, reminiscent of Amrita Pritam’s ‘Pinjar’.

Partition continues to haunt—not just as a bloody chapter of our history but as a lived reality. Many second and third generation writers are exploring it through family histories—intergenerational traumas caused by the brutality of the communal violence and their continued quest for healing. ‘The Parted Earth’ by Anjali Enjeti is about a granddaughter's journey to understand her grandmother's trauma of the Partition. ‘Victory Colony 1950’, Bhaswati Ghosh’s debut novel, is set in the aftermath of the formation of what was then East Pakistan and narrates the crisis of a family rescued by a stranger Muslim.

By Vandana Shukla